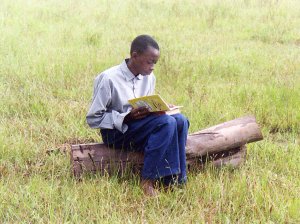

This is a long one! I’d like to share about the village outreach I went on this weekend, as I’ve learned more from this than anything else I’ve done here in Nigeria. Gidan Bege, which means “house of hope”, is an urban ministry of ECWA/SIM. They have a building in town which is a clinic, vocational school, transitional housing for street kids, and a place where the sports ministry is run. It is really an all-purpose place. Gidan Bege every few months or so goes on a village outreach. Someone working at Gidan Bege has a connection in a village somewhere, and they decide that we should go out and minister to that village. They usually go from Friday to Sunday and take their outreach team, which consists of many Gidan Bege workers, volunteers, and senior boys. The street kids, who are orphans literally found living in the streets, grow up in different Gidan Bege ministries, and when they are old enough, they begin to participate themselves in Gidan Bege ministries. It’s absolutely amazing. Some of these boys have the worst stories. They have no families, and often have been abused, were starving and physically pathetic when they were found. They usually have had little, if any education. Gidan Bege takes them in and gives them a life back. To see them now part of an outreach team, reaching out to others who are as needy as they were, boys who are now healthy, studious, happy, and love God---it’s one of the great miracles God has done here. They really were a joy to work with and treated us like we were their long-lost relatives.

It was a very, very typical Nigerian adventure, for sure! It certainly started out in typical Nigerian fashion. First of all, we arrive at 9AM at Gidan Bege with our van packed full of sleeping bags, tents, sound equipment, food and water in a cooler, and our own stuff (very little), expecting to leave soon after we got there. As we pull up, there are about 30 Nigerians standing around outside, near a white van. Many young men between 18-24 years of age, were milling about, many carrying guitars and drums and other random instruments. We get out and greet everyone in the usual long but joyful fashion. There was a team of about 13 Americans who were on a short-term missions trip who were supposed to join us but weren’t there yet. We wait about half an hour, then it turns out that someone thinks we were supposed to go pick them up instead. No one knows what to do, so we try to call the person in charge of the Americans, but we don’t reach them. So we wait another half an hour, then someone decides we should go get them. Our van only has Becca, Marion, and I (Frank is away at a camp), the driver Mark, and Jummai, a health care worker at Gidan Bege. Jummai and Mark decide we should go to the bakery on our way. Then, Jummai remembers we’re supposed to go pick something up from a pastor at Gidan Bege. Well, that something turns out to be two women traveling to a village “near” the one we’re going to and three sacks of some sort of grain! So off we go, about half an hour behind the other vans by now, and 1.5 hours behind total.

We drive for about 2 hours and drop off one lady, then another. It is soon apparent to me that their villages aren’t exactly “close” to our intended village---we backtrack for about half an hour, so now we’re 1 hour behind the other vans. At some corner, we meet the pastor of the ECWA church which is the nearest ECWA church to the village we are going to. He was waiting for us. However, it’s not like there are any directional signs in Nigeria, and this village we’re going to is in the bush somewhere, on a dirt path off the main road. He’s not sure which dirt road they took. So, for about an hour, every couple of small villages, the pastor would pull over, and ask some villagers if they saw two white vans full of white people and Nigerians drive past. We kept going till we found a village where they said the vans turned off onto a dirt road. We picked up two people there who I guess directed us to the village, but we might have been just giving them a ride. We drive for another 20 minutes through what looks like a scarcely inhabited savannah bush area, and how our driver knew which dirt roads to take, I don’t know. But we finally arrive at a decent size village, and all the villagers are standing there, staring at the Americans. They’ve mostly never seen a white person before and hardly anyone speaks English. Though the other two vans have been there for about an hour, they haven’t done anything but greet people. We go to a small hut to eat lunch, and soon, every window and doorway is filled with the villagers staring at us. At least 100 people watched us eat in solemn silence. It’s INCREDIBLY disconcerting to find that everything you do, every word you speak, every move you make, no matter how trivial, is being watched by just about EVERY person in the village. It gives me so much sympathy for the lions in a zoo!

We then set up shop outside of a Catholic church in the middle of town and get to business. The Gidan Bege boys start playing music and entertaining the children. The Americans pair up with other Gidan Bege people and sit in the church to counsel, pray with, and share the gospel with the villagers. Becca, Marion, and I have an interpreter and our own medical stations. Emmanuel, a Nigerian medical student, and two health care workers, Jummai and Mercy, are there as well, for a total of 6 medical stations. The villagers line up outside the church and give their names and requests, and we all start seeing them.

I’m told we saw 240 people that first afternoon. They just kept coming. It’s hard to explain what it was like. Many people have never seen a doctor before, certainly not a white one. The nearest hospital is who knows where, and I didn’t see more than three vehicles in the village. They are all dirty, somewhat or very malnourished, have terrible teeth, and worms. There is one water source not very close, and it is used for bathing themselves, their cars, their clothes, drinking, etc. We didn’t see water the whole time we were there except the drinking water we brought with us. Almost everyone has stomach complaints, a lot because of the worms, and everyone has back aches and headaches. It’s no wonder. They are farmers who work hard, and all Nigerians carry many, many pounds on their heads. We saw many things we could treat, such as ear infections, malaria, rashes, fungal infections, bladder infections, worms, etc, but we also saw many things we couldn’t help. Cataracts, broken bones healed wrong, very, very sick babies, women who had just given birth and were still bleeding and in pain, large livers and spleens, even one cleft lip and palate. Those, we tried to counsel and convince they needed to go to a hospital, but it’s so hard. They don’t have money or transport. But surely some of the ones I saw would die otherwise. Some of those sickly babies looked like they had HIV and I wished I had some HIV test kits with me. In one way, it's so discouraging, to know people might die of things that could so easily be treated if they had the resources. On the other hand, being a medical worker in Nigerian teaches you something you hardly learn in the US: That we are limited beings. We can't save everyone. We aren't meant to. We are meant to heal the best we can, and the rest is up to God. We don't have power over life and death, and if our patient dies, well, we didn't cause him to die. So we learn humbleness, and just be happy with the victories we do have in healing people.

What I actually found most trying was the cultural differences. There were two main problems: the villagers communicate symptoms and dates differently than we do, and sometimes, they tell half-truths or lies to get what they want. For instance, the first few patients I saw, I asked, “what is the problem?” I was told stomach ache. I’d ask my usual set of questions: “where is it, do you have diarrhea, do you have vomiting, do you see blood in either?” The answers I’d get are: “the pain is all over, I have diarrhea, I have vomiting, I sometimes see blood.” I soon learned that I very specifically had to ask, “when was the last time you had blood in your diarrhea?” because the answer was often, “last year”. Or, I learned to ask, “when do you vomit? What do you vomit? How much?” because I’d often get, “I vomit only a little bit of whitish stuff after I ate”, which isn’t really vomit. Sometimes I would ask if they had blood in their urine, and at first they’d say yes, then when I started asking more detailed questions, I’d get, “well, no, I don’t really have blood in my urine”. I don’t know if they didn’t understand my interpreter or if I was asking the question incorrectly, or if they were lying or what. So it became this game of trying to find the right question to ask to get the right answer. Sometimes, they just didn’t know how to answer. They’d tell me they had body pain, but they didn’t know where. I’d ask, “is it your head, or your throat, or your legs, your mouth….”etc, etc, etc, and they’d say no to everything, but still insist they had pain. I would just tell them I can’t treat them if I don’t know what I am treating, but I always gave everyone a course of multivitamins and de-worming pills anyway.

Jummai and Mercy told me that many Nigerians simply don’t know how to answer the question, as in, for some reason, villagers can’t answer straight, and they also said that many of the villagers had nothing wrong. It’s just that most hardly ever see a doctor, and if their neighbor got a pill, well, they want a pill too! They want whatever free thing they can get their hands on, and you can’t convince them they don’t need a cough syrup if they don’t have a cough! If their son gets a cough syrup, then by God, they should get a cough syrup too.

I also learned a few things about myself. After what must have been the 50th stomach ache, headache, backache, and fever I saw in a row, I began to be very skeptical, and very tired of seeing the same thing. I began to suspect that each person had told their neighbor to tell the stupid white person that they had a stomach ache and she’d give you a pill, and they’d all decided to play the same trick. It’s hard to show grace when you’re tired, frustrated, and can’t get a straight answer from anyone. Jummai and Mercy were quite skeptical and often sent patients away after scolding them for coming with false complaints. Since I was sitting by them, I found my skepticism boosted by theirs. Becca and Marion, who were sitting on the other side of the room, were much better at being compassionate and believing the patient. I suspect that the truth again lay somewhere between us---Becca and Marion being a bit too gullible and Mercy, Jummai, and I being too skeptical. At the end of the clinic, I reminded myself that loving my patients was my priority, and resolved to do better the next day and look to the spiritual as well as the physical suffering.

Clinic ended around dinner time, except, there was no dinner! The pastor who sent us to this village hadn’t told the village we were coming, because in the past some villages had been told we were coming and they were all excited and prepared meals and a celebration, and then we had to cancel for some reason, and it was a huge disappointment. So this time, we just showed up without prior notice. So, no one had dinner except Marion, Becca, and I—we ate the same thing we had for lunch, bread with jam, and oranges. During the evening, they set up a screen and had a movie and other visual arts presentations and a man who spoke to the village and prayed for them. He asked how many people were moved by everything they saw and experienced today, and over 200 decided to dedicate their lives to Christ. It is hard to know how many were genuine or were just caught up in the moment, but if even half were sincere, then it was an amazing thing. The ECWA pastor arranges for follow-up, and everyone got together and prayed in little groups with these people. We finished the evening with singing. Nigerians love to sing and sing in wonderful harmony, so it was great.

We slept in tents that had been put up in the middle of town. As we made our way to the tents, the villagers all stood in a circle around the tents and stared solemnly at us again. Becca, Marion, and I tried to find a place to sneak off to in order to go to the bathroom without anyone seeing us (no, there was no toilet or any sort, just the bush and the toilet paper and hand sanitizer we brought) and we ended up having to go far out into the bush and turning off our flashlights so no one could see us. The tents weren’t in great shape so there were holes and I was dreading the mosquitoes coming in. Sure enough, there were mosquitoes all night long in our tent. I decided I’d rather be bitten than put a sheet over me because it was SO hot. We didn’t sleep well---someone was playing the guitar for hours into the night, there was a loud radio somewhere in the village, the dogs were barking, the mosquitoes were buzzing in our ears, and someone in the next tent was snoring VERY loudly, but it was what I expected.

By 6AM the next morning, the villagers were back, standing outside our tents, waiting for us to come out. I can’t describe to you how grubby we felt in the morning---we couldn’t even wash our hands with water, and we had layers of dust, dirt, sweat, sunscreen, insect repellent, and hand sanitizer on. We had a quick prayer/worship time, another trip to the bush, and by 8AM, we were back at our clinic stations. It was much the same as the day before. I was able to be more patient that day. We ran out of many medications by noon, so we quit. The Nigerians were staying another dy, but the American team and the three of us were going home that day. And as usual, we got delayed going home. We meant to leave soon after clinic ended, but one of the American little boys on the team had run off with the village boys to find the water hole to chase around monkeys and was nowhere in sight. Our driver Amos and some Gidan Bege and village kids went to find him. We sat roasting in the car for almost 45 minutes while the villagers stood and stared at us. The kid came back on someone's shoulders, in a throng of Nigerian villagers and Gidan Bege kids like a returning champion. Amos went missing for another 30 minutes until we sent some boys to find him, and finally he came back. So we left, 1.5 hours late in true Nigerian fashion. And of course, we get a flat tire about 1 hour out. We pull over, thankfully near an intersection with a town and not in the middle of the bush somewhere. Most of the men go off to roll the tires to get pumped (the spare was flat too). The rest of us try to stand in the shade, which is still hot, and avoid bugs. After half an hour later they're back, get the tire back on, and off we go. We get home with no more mishaps and thank God for showers that work!